Taylor Smith

Taylor Alaina Liebenstein Smith (b. 1993, Rochester, New York) is an American, French-naturalized visual artist currently based in Oslo, Norway, working between Oslo and Paris. She is currently completing an M.F.A at the Kunstakademiet in Oslo, after completing an M.A. in Cultural Mediation at the École du Louvre in Paris in 2017, a B.F.A. in Painting and a B.A. in Art History from Boston University in 2015. Taylor has participated in several group and solo exhibitions and residencies in France, Finland, Germany, Spain and the U.S. She is also a member of the Bioart Society (Helsinki).

Taylor Alaina Liebenstein Smith (b. 1993, Rochester, New York) is an American, French-naturalized visual artist currently based in Oslo, Norway, working between Oslo and Paris. She is currently completing an M.F.A at the Kunstakademiet in Oslo, after completing an M.A. in Cultural Mediation at the École du Louvre in Paris in 2017, a B.F.A. in Painting and a B.A. in Art History from Boston University in 2015. Taylor has participated in several group and solo exhibitions and residencies in France, Finland, Germany, Spain and the U.S. She is also a member of the Bioart Society (Helsinki).

Since 2014, collaborations with a wide variety of humans and more-than-humans, including scientific researchers (botanists, microbiologists and physicists…), bacteria, micro-algae, lichen, poets, gardeners, landscape designers, fungi, agave and more have become central to her practice. As these international and inter-species collaborations continue to proliferate, her recent works also explore intersections and mis-translations between human languages and other species’ modes of communication.

Interweaving bio art and in-situ, performative practices with photography, video, printmaking and sculpture, her practice ultimately seeks to exist in the fragile, transient space occupied my memory, as it hovers both materially and conceptually between decay and regeneration.

Taylor has been awarded the ART2M/Makery slow mobility grant as part of the Rewilding Cultures programme in 2023. Rewilding Cultures is co-funded by the European Union.

A familiar veil

Project summary

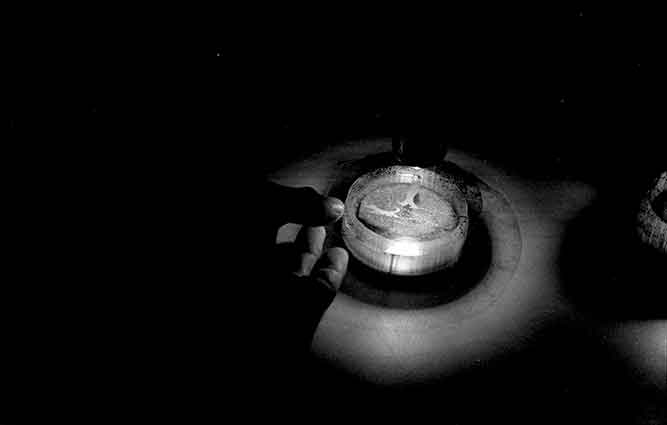

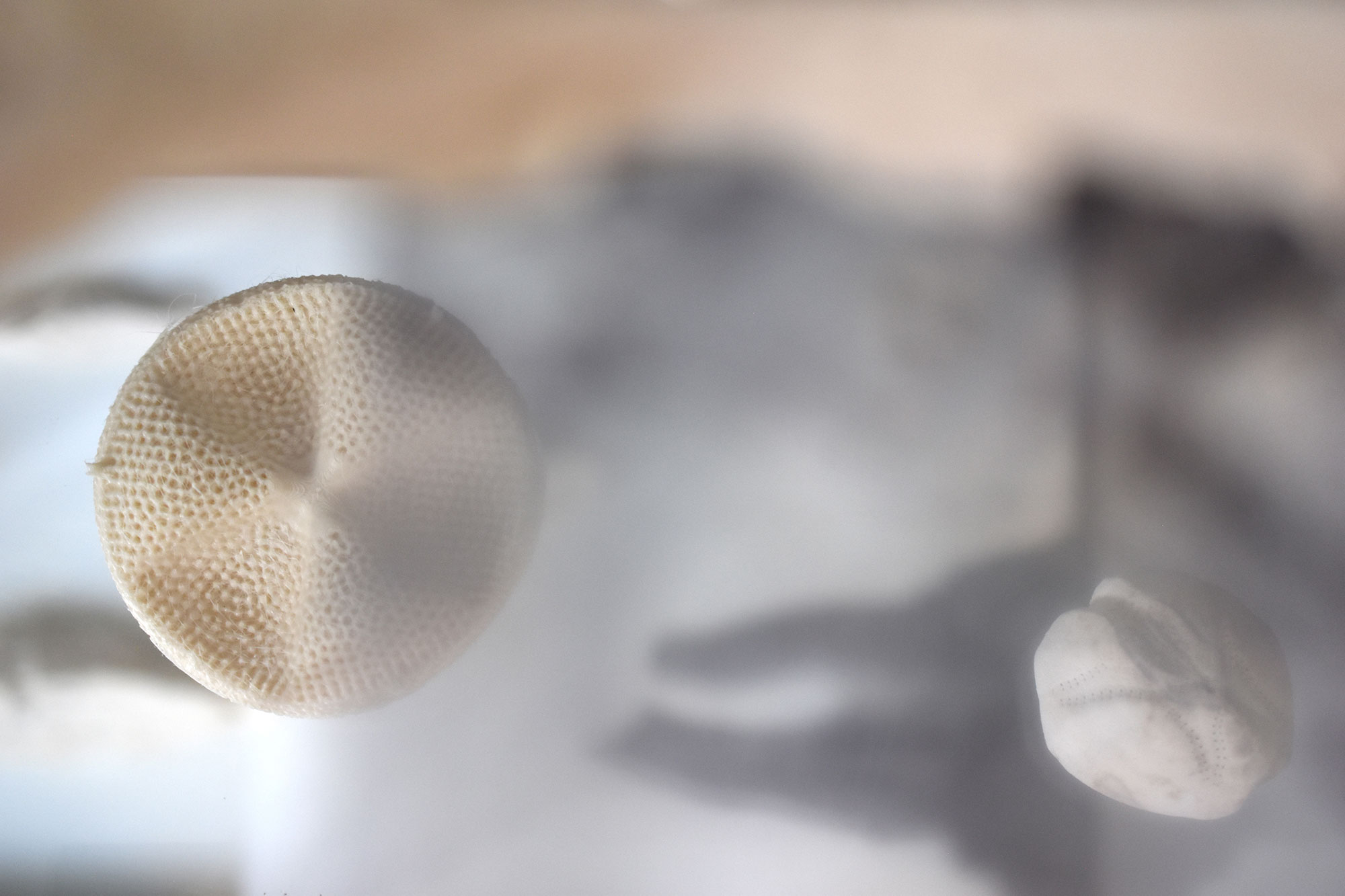

Microscopic photograph taken by the artist at the station marine de Concarneau

A familiar veil is the title of both a poetic video triptych and a broader three-year project, begun during an art-science residency at the marine biology research station of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (MNHN- the French National Natural History Museum) in Concarneau, via a collaboration with marine microbiologist Cédric Hubas. It then traveled to Kilpisjärvi, Finland, Sandøya, Norway and Strückhausen, Germany: rural landscapes that carry a personal importance for me and my ancestors, both human and more-than-human. In each place, human memories (in the form of text or image) were collected from local residents, and subsequently “revealed” in living photographic form, thanks to the photosensitive microorganisms collected in the same places. In the video triptych, a form of visual poetry is composed from this process of bringing memories back to life, accompanied by the voice recordings of four women from four different generations, who recite their respective memories. Each memory is told in-situ in its landscape of origin: French, Finnish, German or Norwegian. The triptych thus reveals the inextricable connections between different space-times, and the natural phenomena, microbial life forms, and embodied materiality of the memories that inhabit them.

The collaboration with Cédric at the MNHN, which began this international and inter-species project, just ended with a series of micro-performative workshops at the Marinarium, the museum attached to the Concarneau marine station, on September 28. I was also invited to present this project in an exhibition and conference at the Natural History Museum’s central location in Paris, from October 7-13. I showed the video triptych A familiar veil, in addition to the photographic archives and a series of mimetic, biodegradable objects that accompany it, within the Bioinspire-Muséum Studio, an ephemeral space installed within the MNHN’s botanical gallery during the fête de la science.

After moving from Paris to Oslo, Norway in October 2022, the Rewilding Cultures mobility grant offered by Makery.fr and co-funded by the European Union enabled me to return to France to finish the project without taking a plane. Given the project’s nature, situated between contemporary art and ecology, it felt essential that I reduce my carbon footprint as much as possible for this Oslo-Concarneau-Paris-Oslo journey, completed entirely via train and boat.

Analog photographs from the archives of A familiar veil : a memory revelation workshop participant at the Marinarium de Concarneau with the video work A familiar veil, Part I and her memory being revealed in the biofilm in the background

Introduction

The video triptych A familiar veil, and the photographic archives and mimetic sculptures that accompany it, constitute a poetic bioart project, which articulates itself across different scales. This collection of works is the result of a form of collaboration between humans and photosensitive microorganisms, particularly diatoms (micro-algae) and bacteria. If we incite them to do so, microorganisms can in fact act as mediators between humans of different generations. They enable us to form alternative perceptions of the links between ourselves and our dead ancestors, or to humans situated in other space-times, to whom we are inevitably connected. As we observe these inter-human links appear within the photosensitive bodies of microorganisms, it becomes impossible to ignore the connections we develop, and already possess, to the microorganisms themselves. This process of revealing our own human memories, in the form of a photographic film woven by these microscopic beings, visualizes layer by layer the infinitely complex mesh of species that constitutes the landscapes we inhabit, and the memories we project onto them.

Biofilm is a very broad term used to describe a collective matrix of (photosensitive) microorganisms. It is a breathing metaphor of living memory: it incarnates both the undeniable materiality of memory, and its elusiveness. As humans, we are condemned to see the world through the veil of our subjective and fleeting memory: the matrix of stories it weaves, drawing on the material reality of the landscapes that surround us. Beyond this veil of memory, we exist thanks to the presence of another veil we tend to ignore : that which is woven by microorganisms. This microbial veil covers every internal and external surface of these same landscapes, as well as our bodies, thus intertwining itself inextricably with the veil of memory.

This project can thus be conceptualized as a veiled portal: a forever partial opening towards interspecies communication, or more broadly to biosemiotics, via an intuitive, sentient, material, corporal approach… one that must pass through our human eyes and hands before it can reach our thoughts.

Biofilm as a metaphor for memory: its elusive materiality

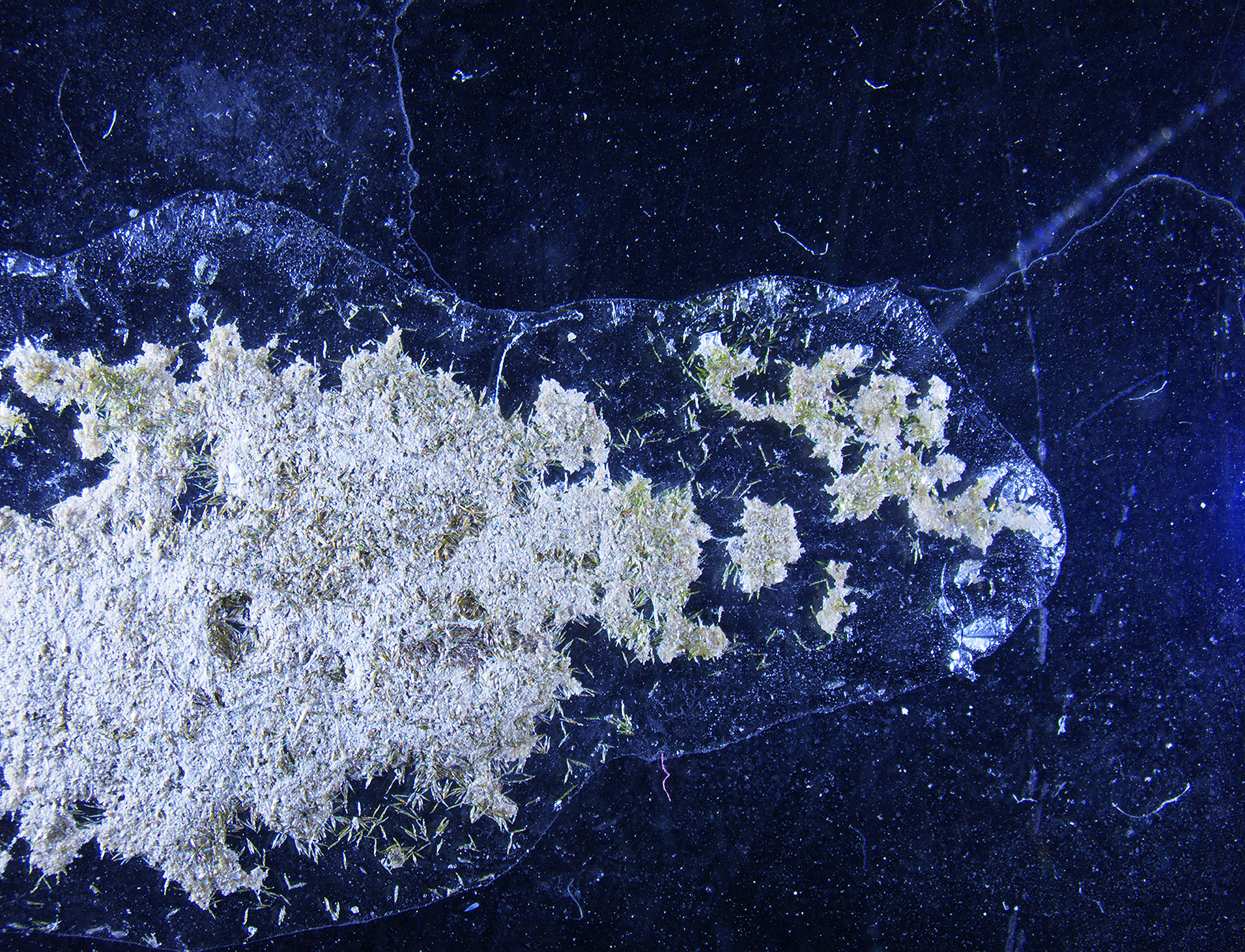

Microscopic photograph taken by the artist at the station marine de Concarneau

In order to better explain the scientific roots of the project, I’ll first attempt to define biofilm, the specialty of my collaborator, Cédric Hubas. In biology, biofilm or “microbial mat” is a broad term. Cédric focuses primarily on what are referred to as “epibenthic transient biofilms” of the intertidal zone: the elusive biofilms of mudflats, which attach themselves to the surface of the mud when the tide recedes, only to dissolve back into the water when it returns.

Biofilm is just as difficult to grasp with words as it is with our hands. It is both a material and living matrix that finds itself in a perpetual in-between state: solid/liquid, night/day, individual/community, aquatic/terrestrial. It is a layer of life composed of microorganisms, held together by the natural glue of “EPS” proteins and lipids in a symbiotic net. Sometimes this net, or matrix, is stuck to a surface, such as a rock, or the linings of our drainage pipes and bones… other times it floats freely in the ocean.

Cédric describes the biofilm matrix in his own words, “A matrix (from Latin “matrix” derived from “mater”, or mother) is an element that offers support and/or structure, that surrounds, reproduces or builds. In microbiology, the term designates more specifically a dynamic and protective environment in which microorganisms grow and move. Another important detail, this matrix is produced by the microorganisms themselves. It’s within this context that my research has developed for several years. The microorganisms that populate these matrices are typically photosynthetic, and I am thus primarily interested in their sensitivity to light, their photo-physiology and their migratory behavior, stimulated by light.”

The hand of a workshop participant trying to grab the biofilm, memory revelation workshop, Marinarium de Concarneau

At the origin of life on Earth, 3.5 billion years ago, diverse aquatic biofilms began to evolve slowly and subtly. They finally managed to anchor themselves to rocks, forming a marine crust: the stromatolite, then finally a terrestrial crust: biocrust. Biocrust, this “living skin of the earth” (Cf. Fernando Maestre) is often composed of photosynthetic, and photosensitive, beings (lichens, cyanobacteria, etc.) and illustrates the terrestrial traces of our aquatic ancestors. Lacking roots, over the course of our planet’s long history, biofilms have been violently ripped from Earth’s solid surface, dispersed in water, re-formed and, sometimes, hardened into biocrust.

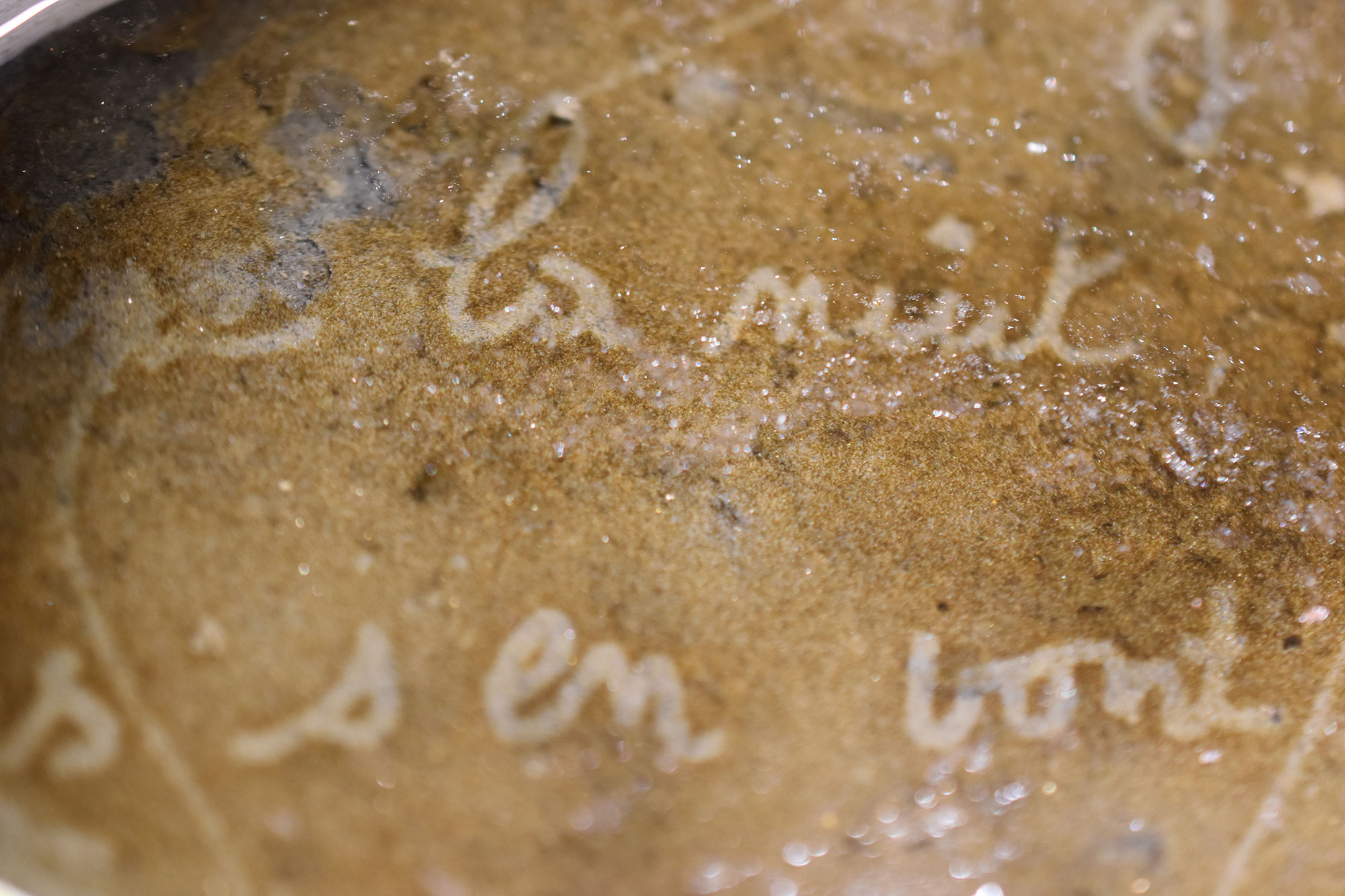

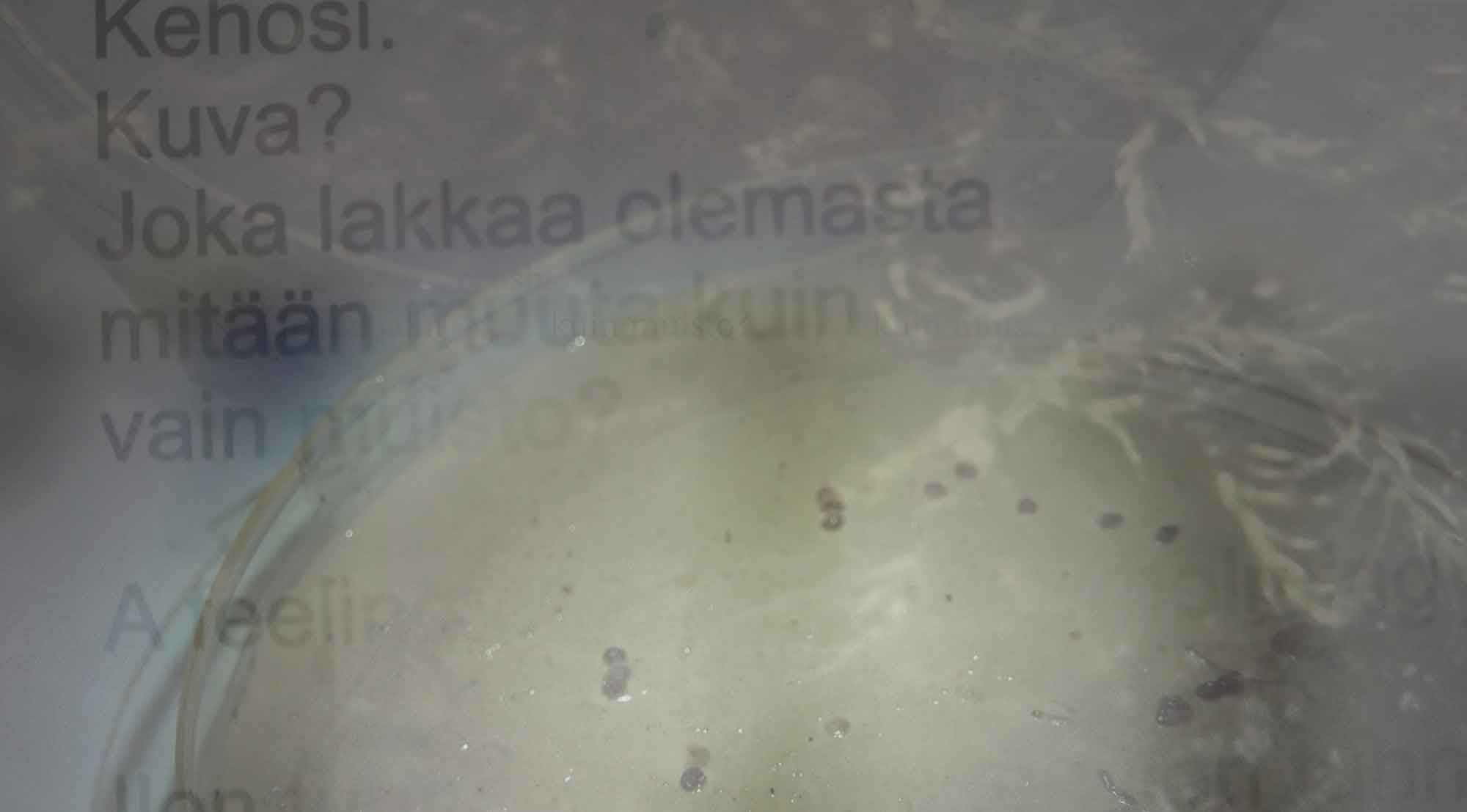

Detail of a petri dish: a memory (text) of my great-grandmother revealed in the biofilm generated by photosensitive bacteria collected from her family tomb in Strückhausen, Germany

In the face of climate change, biofilm and biocrust remain communities of numerous bio-indicator species. They still cover our planet like a luminous skin, a photosensitive film that captures the imprints of everything else, including our destructive human activities.

A bit like the famous deep scattering layer, which migrates in synchrony from the depths of the ocean to its surface at night, only to re-descend at daybreak, diatoms, (the photosensitive micro-algae which compose the biofilm studied by Cédric), also migrate in correlation to the Circadian rhythm. They move up and down within the biofilm matrix according to this 24-hour cycle, a predictable movement that can be perturbed by the more random variations of natural and artificial light in their environment. Diatoms are, simply stated, photosensitive, which for us means that they spend their lives revealing and erasing images. Cédric and I attempt to use light to interfere at precise moments in the Circadian rhythm, in order to make the diatoms’ hidden images visible, and also to project our own images onto them.

Revealing images through the biofilm’s photosensitivity

Detail of a participant’s memory (text) being revealed during a workshop, Marinarium de Concarneau. A brownish-red carpet is formed by the diatoms (brown micro-algae) in the black areas of the negative. This is where the diatoms are too sheltered from the light and must therefore migrate to the surface to find it. Another bluish gray carpet (the color of the mud) appears in the transparent areas of the negative. This is where the light traverses to touch the diatoms, thus inciting them to hide from the light in the mud. The contrast between the brown and blue-gray carpets transposes the negative image, or in this case, the participant’s memory

Artistic research in Concarneau: agar agar molds and 3D scans

Analog photograph from the archives of A familiar veil : double exposures of photographic revelations in the laboratories and during workshops, station marine de Concarneau

In order to pursue my research with Cédric, I was welcomed as an artist-in-residence at the marine biology research station of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (MNHN) in Concarneau, France. The residency was divided into four visits, spread between February 2022 and September 2023. With Cédric and his team, particularly Caroline Doose and Élisabeth Riera, I explored the role of these infinitely small, forgotten beings that compose biofilms as image-makers, attempting to collaborate with them in order to intervene subtly in-situ, via a series of micro-performative gestures.

Analog photographs from the archives of A familiar veil : double exposures of mimetic objects (diatoms)

I began by carrying, for example, photographic negatives holding traces of my own memories (in the form of text or image), with me into various landscapes, in search of microcosms inhabited by photosensitive biofilms. I stopped, for instance, at the tidal pools and mudflats around the marine station and the Atlantic coastline. Via encounters between light, biofilm and the negatives, a series of “micro-revelations” of these memories took place. I captured these fleeting moments via photography (analog and digital) and video, in order to create longer-lasting artworks.

I then repeated these experiences in-situ in other landscapes in Norway, Finland, and Germany, incorporating others’ memories that were more specifically tied to these landscapes. Through this accumulation of experiences and my research and conversations with Cédric, Caroline, Élisabeth and other researchers at the station marine, the initial project began to expand. I began to mold the tidal pools— these concave niches where I found the biofilm growing naturally— in agar agar, a biodegradable powder made from algae of the gelidium family, which transforms into a solid gel when heated in water. Agar agar proved to be the perfect material for in-situ casting, since it captures all of the minute details of an object without leaving any polluting traces. These experimentations captured the attention of Élisabeth Riera in the context of her research on new forms for artificial reefs. We began working together to 3D scan natural and synthetic objects that the biofilm covers: algae, tidal pool crevices, and boat relics that remain buried in mudflats until they’re revealed at low-tide. With the marine station’s 3D printer, and though a collaboration with the Konkarlab, the fablab of Concarneau, I began 3D printing a series of mimetic objects with PHA, a biodegradable 3D filament both generated and composted by other bacteria.

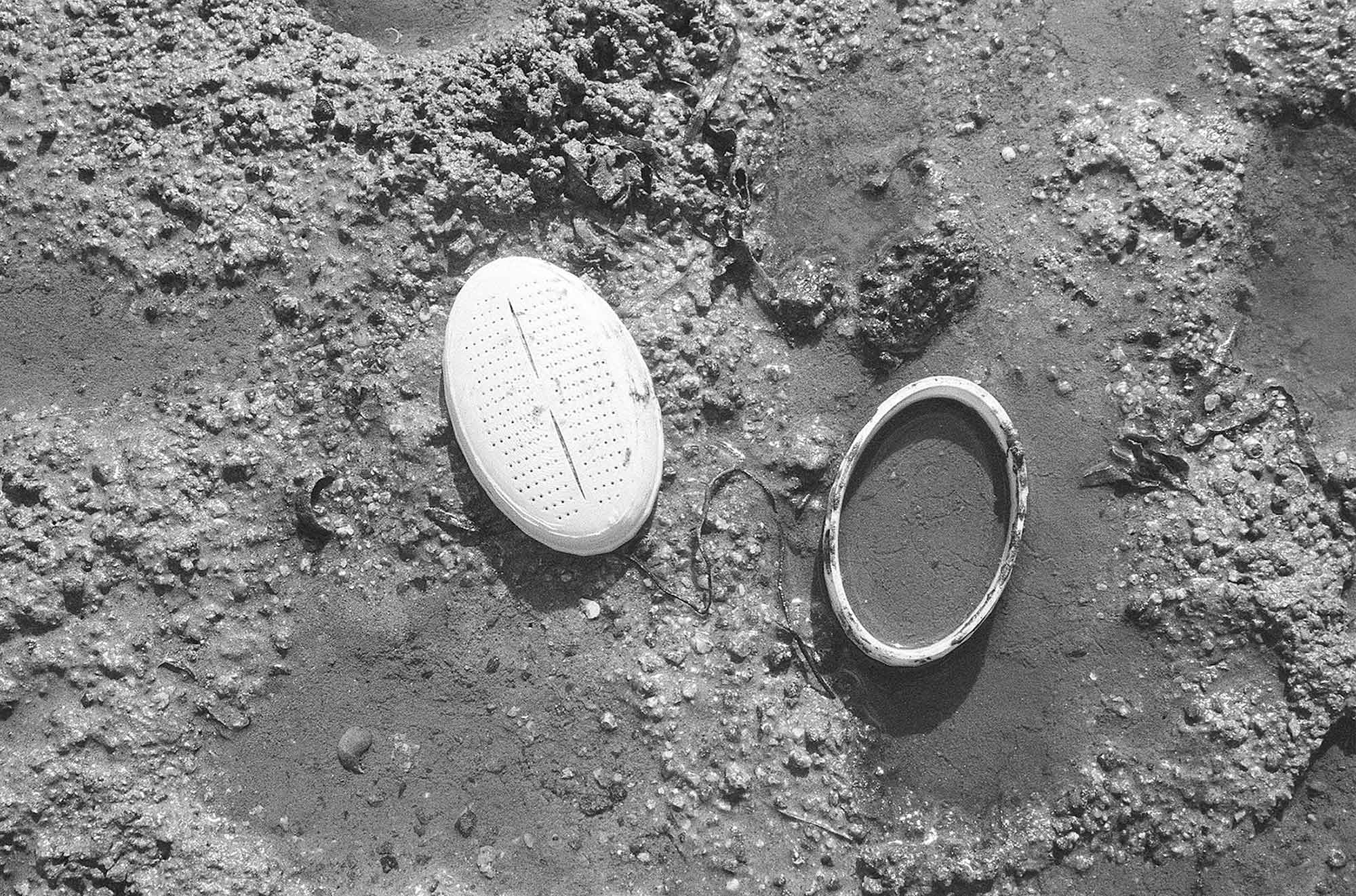

Analog photographs from the archives of A familiar veil : “memory holder” printed in PHA holding mud (and biofilm), near the station marine de Concarneau

Thanks to pre-existing open-source 3D models, I was also able to print reproductions of frustules, or the silica (glass) shells of diatoms that protect their photosensitive bodies, on a larger scale. As one can see in the SEM (scanning electron microscope) images, these frustules naturally take on box or container-like forms, with extremely detailed patterns. Similar to sarcophagi or various precious boxes we use to hold our memories, these mimetic objects became “memory holders” or sculpture-containers for the biofilm, used during a series of memory revelation workshops I organized at the Marinarium.

SEM photograph of a diatom taken by Aïcha Badou, station marine de Concarneau

The workshop and final exhibition

Children touching mimetic objects in agar agar and PHA during a workshop, Marinarium, Concarneau

In April and September 2023, I led three memory revelation workshops with the public at the Marinarium, the museum attached to the Concarneau marine station. The participants (children and adults) were invited to each send me a memory of choice, in the form of a drawing, text or photograph. I then transformed each memory into a photographic negative, which was placed by the participant over one of the biodegradable containers (molded in agar agar or 3D printed in PHA) in the form of a diatom frustule, holding the biofilm. Placed below LED lights, these containers were then exposed to light and the participants watched as, little by little, their memories re-appeared on the surface of the biofilm. The memories were either reproduced identically, reinterpreted, or erased by the photosensitive diatoms, depending on many uncontrollable factors. The unpredictability of the experience contributed to its magic, and the participants’ understanding that this was indeed a collaboration with living beings, and not the simple illustration of a photographic technique.

This photographic revelation experience took place in an immersive environment. The video triptych A familiar veil was presented in the background on three screens, which participants could watch during the waiting periods of the workshop. The dimly-lit room, the view of the ocean and the outdoor fish tanks where the biofilm was collected, as well as the placement of mimetic objects around the room contributed to the scenography of the experience. With Cédric, we also presented the scientific and artistic aspects of the project. It became both an individual and collective experience of discovering the magical behavior of these photosensitive microorganisms.

Finally, the photographic archives, memory holders and other mimetic objects and video triptych were then transported to Paris to be shown at the Bioinspire-Muséum Studio, an ephemeral space installed in the botanical gallery of the French Natural History Museum during the fête de la science (October 7-13).

Detail: objects in a vitrine I curated for the final exhibition of the project at the Studio Bioinspire-Muséum, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris: a crustacean skeleton next to a 3D printed diatom (PHA)

The video triptych A familiar veil

The central artwork resulting from this project is a video triptych, in which the “memory revelation” via the biofilm matrix experienced by workshop participants travels to other international landscapes. Each video opens up a new chapter, where the relationships between human memories and photosensitive microorganisms multiply.

Part I. Concarneau, 8:16”

Views of the video installation of A familiar veil, Part I at the exhibition Circades, Le 6b, Saint-Denis (Paris), France. Curated by Espace fine collective. 15/09- 06/10/2022

Part I of the video triptych is presented as an immersive installation, and serves as the background for a set of “memory revelation” experiences. It operates as a sentient introduction to the biofilm matrix, and how its materiality evokes the equally complex, evolutive matrix of human memory. It is conceived as a poetic, cyclical composition of words, images and gestures, which reveal my discovery of the capacity of photosensitive biofilms to generate living images and texts in-situ, and the Circadian rhythm dictating their migrations. The second and third parts of the triptych explore the same process, applied to more specific human memories in Norway, Finland and Germany, adding layers to a set of multi-temporal experiences in different microbial-human milieux.

Part II : Kilpisjärvi, 13:14″

Filmed at the Kilpisjärvi Biological Research Station (University of Helsinki) in Kilpisjärvi, Finland during the Ars Bioarctica residency program, run by the Bioart Society and at the Atelier Bo Halbirk, Paris, France. Video montage completed at Atelier Nord, Oslo, Norway

Part II takes place in Kilpisjärvi, Finland. My own voice and that of Finnish environmental artist Leena Valkeapää recount two intersecting narratives. The first is a memory of light, told by Leena, who meditates on her experiences of reindeer-herding under the aurora borealis. The second text is my own, also written while in Kilpisjärvi, in response to the visceral connection I felt to this subarctic landscape— a kind of memory told in the process of forming. The footage in the video works mixes various attempts to materialize the immaterial veil of memory, whose presence can be sensed in any landscape, and whose visual form mutates constantly according to the subjective experiences of the viewer, placed both spatially and temporally within that landscape. Throughout the video triptych, I interpret this veil of memory as a living layer that covers everyone and everything: I imagine its materiality as a kind of skin-like substance similar to the sticky, liquid texture of the biofilm matrix. Sometimes, however, this veil of memory takes on the more consistent texture of other living layers that cover the Earth’s surfaces, such as biocrust. In this video work, I also use man-made veils such as transparent fabric, photopolymer film, and other (primarily photosensitive) synthetic materials to repeatedly veil and unveil fragments of the landscape on different scales. My hands are also shown sampling colorful, photosensitive bacteria from the Kitsiputous waterfall in Kilpisjärvi, which I collected via a collaboration with microbiologist Minna Männistö during my first stay at the Kilpisjärvi Biological Station. I then cultivated these bacteria in petri dishes and exposed them to UV light under photographic negatives. The negatives, much like in Part I of the triptych, reveal printed texts and images: fragments of the memories collected from Leena and myself. At the end of the Ars Bioarctica residency in Kilpisjärvi, the contents of the petri dishes were returned to the locations they were taken from, left to decompose.

Part III. Sandøya- Strückhausen- Paris, 18:28”

Part III adds a final layer of memories to be revealed within the biofilm matrix. This last work follows my own three-day journey traveling back through Paris by train to reach Concarneau from Oslo, Norway, where I moved in October 2022. The journey begins a few hours south of Oslo on the island of Sandøya where my aunt, Laurie Vestøl lives. In Sandøya, I serendipitously discovered another photosensitive aquatic biofilm — seemingly identical to the one studied by Cédric Hubas at the marine station in Concarneau— in the shallow waters surrounding the island. During the same visit, my aunt informed me of the existence of my German great grandmother’s archives: poems, songs and letters she wrote throughout her life, some of which were stored in Sandøya. Given the photosensitivity of this newly discovered biofilm in Sandøya, the idea to photographically reveal, or literally bring her texts back to life there, in-situ, thus came about naturally. I chose one text in particular from her archives to reveal: the ballad Das Gewitter (The Thunderstorm), originally written by Gustav Schwab in 1828 and transcribed in my great grandmother’s handwriting at an unknown date during her life. The ballad is based on a true event that took place on June 30, 1828: lightning struck a home, killing four women of four generations— referred to as child, mother, grandmother and ancestor in Schwab’s text. For the video work, I recorded my German friend Nora Assendorp reading Das Gewitter out loud, and transcribed her translation to English. I was struck by the melancholic tone of the ballad, and how it could be interpreted in the context of the ecological crisis: four generations of humanity killed in an instant by a natural phenomena. The incredible fragility and short time scale of human life, even whilst spread across four generations, is made strikingly clear in Schwab’s text.

The discovery of this ballad led me to the final woman whose memory I was to collect and reveal within the biofilm matrix: Françoise Pelet. Naturally, the four women whose memories are revealed in the video triptych are of the four different generations, like the women of Schwab’s ballad: myself – granddaughter (b. 1993), Leena- mother (b. 1964), Françoise- grandmother (b. 1937) and my great grandmother or “ancestor”- Anna Purrnhagen (1900-1993). Each of us, however, was born in a different country and, apart from Anna Purrnhagen and I, are not blood relatives. Françoise recounts her memories of the Liberation of Paris, as a six-year old girl forced to overcome her fear of the Germans. Juxtaposed with my German great grandmother’s transcription of Das Gewitter, and the equally melancholic tone of her letters describing her own childhood growing up in rural northern Germany during World War I, the two stories are woven together across the final two generations of the triptych.

My own hands are also shown in the video sampling photosensitive bacteria from the lichen that colonize the family tomb of my great grandmother’s descendants, in her native village cemetery in Strückhausen. I then use these bacteria to repeat the same photographic revelations performed in Sandøya. The Strückhausen bacteria were cultivated in petri dishes, thus forming a new biofilm, and then exposed to UV light, projecting my great grandmother’s transcriptions of Schwab’s poem directly onto the bacteria from her birthplace. I continued to materially re-interpret this text by re-transcribing my great-grandmother’s handwriting directly into the biofilm growing in the petri dishes. I also made frottages of her texts, rubbing charcoal onto paper pressed onto the Purrnhagen family tomb in Strückhausen. These frottages, which also appear in the video, show an attempt to merge the physical traces of the biocrust growing on the Purrnhagen tomb, and my great-grandmother’s cursive handwriting. Lastly, to complete the cycle, I revealed selected texts from Françoise’s memories within the biofilm of Concarneau, thus completing the project where it began. A filmic superposition of this repetitive photographic revelation process of living memories in all four countries, with all four women’s memories, is what constitues the triptych’s poetic composition.